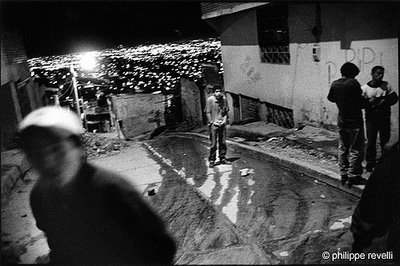

Writing in 2000, a period during which the FARC still enjoyed state-sanctioned control of large swathes of South-Central Colombia marked out as a "zona de despeje," a cleared zone, Alma Guillermoprieto notes the grubby normality of everyday life in this safe haven. In San Vicente de Caguán, "there are loud cantinas; fleshy women in too much makeup under the glaring sun; block after block of storefronts selling boom boxes, high-heeled shoes, glitter eye shadow, and telephones shaped like hot dogs" (Looking for History 55).

Writing in 2000, a period during which the FARC still enjoyed state-sanctioned control of large swathes of South-Central Colombia marked out as a "zona de despeje," a cleared zone, Alma Guillermoprieto notes the grubby normality of everyday life in this safe haven. In San Vicente de Caguán, "there are loud cantinas; fleshy women in too much makeup under the glaring sun; block after block of storefronts selling boom boxes, high-heeled shoes, glitter eye shadow, and telephones shaped like hot dogs" (Looking for History 55).The guerrilla, as far as Guillermoprieto can see, spend their time mostly lounging about: buying mascara and nail polish; chatting with neighbours; watching TV, their FALs and AK-47s casually propped up in the corner of the room. Of course, the point about a safe haven is that it's a good place for a little R&R; it's not as though there's no war on, and indeed with up to 20,000 people under arms, the FARC are able to carry out significant actions, "waging something very like real war against the Colombian state" (60). (And here's a pretty good round-up of recent accounts of "Latin American's Longest War".) But even this war has become very much a habit among its combatants, some of whom have known little else than life as a guerrilla.

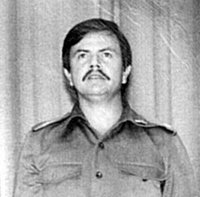

For instance, compañera Nora, "a trim, agreeable woman in charge of the FARC's liaison with the public" (57) has spent well over half of her thirty-three years in the rebel ranks. Meanwhile, the insurgent leader, Manuel Marulanda or "Tirofijo", has been out in the hills in one form or another since the "Violencia" of 1948 to 1958. In Colombia, civil war is very much a way of life, for some almost a lifestyle option: Nora is reported as saying that she joined the FARC, at the age of fifteen, after she had seen a guerrilla column with its "brisk young women, in uniform and carrying guns, and thought they were the most powerful and glamorous creatures she had ever seen" (59).

At the time of Guillermoprieto's visit, the FARC and the Colombian government (under President Andrés Pastrana) were engaged in a "peace process," though these are hardly exactly peace talks: they are rather a "ritual encounter" celebrated "on a regular basis, and call[ed] progress" (64). No real dialogue was underway, and in any case everyone knew that at the margins prowled the military and their comrades in (para)military arms, the so-called "self-defence" units.

But in any case, such hope as Guillermoprieto entertains is based on the notion that the FARC's experience in this demilitarized zone might bring about a rehabituation. In that they had not been granted sovereignty of this territory that was often misleadingly nicknamed FARClandia, Guillermoprieto notes that ""for the first time, the guerrillas are coexisting with the citizens of a small town, and even having to get along with its mayor" (66). The rebels are forced, in their downtime, at ease, to be "sharing social and political space with the inhabitants of San Vicente" (68).

But in any case, such hope as Guillermoprieto entertains is based on the notion that the FARC's experience in this demilitarized zone might bring about a rehabituation. In that they had not been granted sovereignty of this territory that was often misleadingly nicknamed FARClandia, Guillermoprieto notes that ""for the first time, the guerrillas are coexisting with the citizens of a small town, and even having to get along with its mayor" (66). The rebels are forced, in their downtime, at ease, to be "sharing social and political space with the inhabitants of San Vicente" (68). For Guillermoprieto, then, the experience is a lesson in conviviality, that takes place at a level well below the comandantes non-negotiations with their official counterparts, and even well below the ideology that in any case is hardly the rebels' motive force.

This is not to say, however, that this process of conviviality is not connected in some way with the media--though it may not be mediated in any conventional sense. For Guillermoprieto ends her account with what we are to take as a hopeful sign: a sudden realization that comes to her on her last morning, as she is taking breakfast at a fonda, or small restaurant, abutting the local FARC headquarters. A television is on, as in Latin America one always is. And the programme playing was Xena: Warrior Princess, the TV industry's ironized take on fighting women. But this irony establishes, perhaps, some common ground:

Two waitresses, as young as the guerrillas next door, were glued to the program. And then I realized that the guerrillas were too. The FARC videos were still playing just on the other side of the wall, but the kids were taking turns sneaking out of the headquarters to stand at the doorway of the fonda, watching Xena. (71)Of course, as a postscript acknowledges, just a couple of months later the US Congress approved "Plan Colombia". And by early 2002, the state withdrew its support for a demilitarized zone, the army returned, and so disappeared any hope for Xena-blessed conviviality.